Atlas

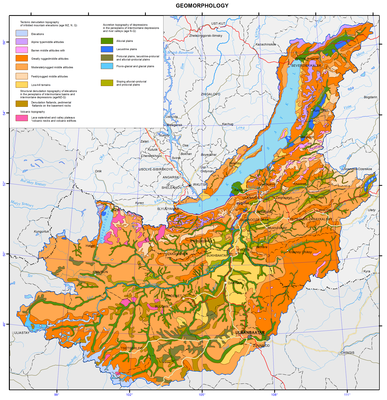

010. Geomorphology map

Geomorphology

The Baikal basin is located in the center of Eurasia, which determines its specific traits as well as the main features of nature. Paleogeography and geology of the region govern its peculiar landforms.

Vertical tectonic movements of the Late Mesozoic and the Cenozoic developed a mountain-basin type of topography.

The orographic structure of the Baikal basin is rather complex. The topography as a whole is a unified Pliocene-Quaternary formation [Ecosystems, 2005]. Significant subsidence of individual blocks in the midst of general uplift developed grabens of two types. The first type (the Baikal type) is associated with the intensification of tectonic activity in the inland Baikal Rift Zone. The amplitude of vertical neotectonic movements, as well as the thickness of loose deposits reach their maximum here. Crustal movements in this area are still quite intense; they cause a high seismic activity with frequent and sometimes strong earthquakes. The second type (the Transbaikalian type) is represented by wide intermountain lowlands, which are very common in the Selenga river basin. They formed as a result of recent deep-seated tectonic dislocations superimposed on the rejuvenated Mesozoic depressions.

Intermountain basins are separated by mountain ranges varying in height and geological structure. They are noticeably dissected by exogenous processes of erosion.

In the Quaternary, the highest orographic units (the Baikalsky, Verkhneangarsky, Barguzinsky, Khamar-Daban, Khangai and other mountain ranges), especially their north-western and northern slopes, were exposed to glaciation, which is indicated by the presence of the alpine landforms (cirques, avalanche chutes, through valleys, moraines, etc.)

Both positive and negative landforms within the Selenga river catchment area basin and up to the Uda river mouth are generally directed northeastward with a dominant altitude lowering northward. The mountains surrounding of three Baikal intermountain basins (Barguzin, Verkhneangarsk and Khovsgol lowlands) are characterized by higher absolute altitudes and deeply cut river valleys. These factors predetermine a wide range of elements typical of mountain landform, or plain landform in the wide intermountain basins.

According to the geomorphological zoning [Highlands…, 1974; National Atlas of the Mongolian People’s Republic, 1990] the area of the Baikal basin is made up of the following features: Khangai and Khentei-Dauria highlands, Khovsgol mountains, Orkhon-Selenga middle mountains and its continuation in the north - Selenga (Selenginskaya Dauria) middle mountains, mountain systems of the Dzhidinsky mountainous region, mountain ranges of Khamar-Daban, Ulan-Burgasy, Ikatsky, Barguzinsky, Verkhneangarsky, Severomuisky, Baikalsky, and Primorsky, and the western side of the Vitim Plateau. Minimum absolute altitude is the Lake Baikal waterline; since it is regulated, it is subjected to slight fluctuations at around 460 m a.s.l. Maximum absolute altitude is 3,539 m a.s.l. (the Khangai Highland).

The highest mountain range in the area is the Khangai Highland located in the south-western part of the basin; it has generally subdued delineation and slight changes of relative altitudes. The mountains become more prominent towards the central part of the basin due to Alpine landforms. Tarbagatai and Telin-Tsagan are the largest northern spurs of Khangai Highlands with individual peaks reaching 2,500 m.

The maximum altitudes of the Khentei Highland mountains go up to 2,200-2,400 m a.s.l. Their wide and long spurs stretch westward and eastward, forming a large highland, gradually descending to low hills in the west and in the south, and joining the mountains of Transbaikalia in the north. Generally, this is a gently sloping landscape with wide-spread residual hills, rocks, and scattered stones. Traces of ancient glaciation are preserved to a limited extent.

The Orkhon-Selenga middle mountains are located in the central part of the watershed basin between the ranges of the Dzhida river basin in the north and the Khentei Highlands in the south. It features a flattened relief and its spatial configuration resembles a huge amphitheater descending towards the northeast.

The Selenga middle mountains consist of sublatitudinal medium-altitude mountain ranges with rounded summits (Tsagan-Daban, Borgoisky, Chikoysky, Tsagan-Khurteisky, Zagansky, and others) separated by wide intermountain valleys distinctly stretching along the main riverbeds. The valley bottoms are drained by the Selenga tributaries (Chikoy, Khilok, Uda, Dzhida) and composed of alluvial and proluvial deposits of different age arranged in terraces and wide piedmont plains. The Selenga river valley lies among low hills with granite residuals, rocks, and cliffs.

The Khovsgol area relief has a complex structure. Its west side features sharp-crested, steep-sided, and hard to access ridges of Bayan-Ula and Khoridol-Saryag. The outlines of the mountains to the east of Lake Khovsgol resemble those of the northern Khentei with altitudes over 2,000 m. Extensive Late Cenosoic lava plateaus are specific features of these mountains.

The Dzhida and Khamar-Damban Mountain Ranges have a lot in common. They stretch from the south-west to the north-east. In the west, they are relatively flattened and marked by bald peaks, gradually turning into the alpinotype middle mountains of the Big Khamar-Daban Mountain Range, which drops steeply to the shores of Lake Baikal. In the east, the mountains have a lower altitude. The Selenga river cuts through their spurs.

The northern part of Lake Baikal and the Verkhneangarskaya basin are surrounded by Alpine landforms with harsh outlines of the axial and piedmont parts of the Baikalsky, Verkhneangarsky, Severomuisky, and Barguzinsky mountain ranges. In spite of the relatively moderate elevations, there are many glacial traces here, and in some places there are small vanishing mountain glaciers (e.g. the Chersky Glacier – about 0.4 km2) The Vekhneangarsky basin relief shows little elevation changes at the bottom. It is formed by the alluvial deposits of the Verkhnyaya Angara (the Upper Angara) river, and by lacustrine alluvial deposits of paleobasins. Extensive proluvial and fluvioglacial piedmont plains are typical of the basin.

The structure of the Barguzinskya basin is typical of the Baikal-type depressions: large swampy plain areas at the basin bottom, and relatively uplifted ancient alluvial lacustrine terraces made of sandstone deposits. The presence of large areas of sandstone deposits predetermines high eolian activity.

In the south, the Barguzinskaya depression is framed by massive, but relatively flat landforms of the Ikatsky range. The highest summits of the Ikatsky range as well as those of the ranges lying further south (Ulan-Burgasy and Kurbinsky ranges) are treeless and flat with mountain terraces.

References

Logachev, N.A., Antoshchenko-Olenev, I.V., Bazarov, D.B. et al. (1974). Highlands of Cisbaikalia and Transbaikalia. Moscow: Nauka, 360 p.

Ecosystems of the Selenga basin (Biological Resources and Natural Conditions of Mongolia: Proceedings of the Joint Russian-Mongolian Complex Biological Expedition; vol. 44), (2005). Executive Editors: E.A. Vostokova and P.D. Gunin. Moscow: Nauka, 359 p.

Document Actions

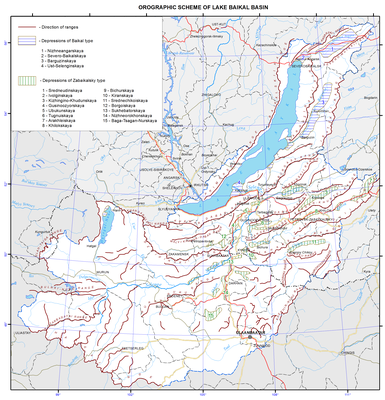

011. Orographic scheme of Lake Baikal basin map

Geomorphology

The Baikal basin is located in the center of Eurasia, which determines its specific traits as well as the main features of nature. Paleogeography and geology of the region govern its peculiar landforms.

Vertical tectonic movements of the Late Mesozoic and the Cenozoic developed a mountain-basin type of topography.

The orographic structure of the Baikal basin is rather complex. The topography as a whole is a unified Pliocene-Quaternary formation [Ecosystems, 2005]. Significant subsidence of individual blocks in the midst of general uplift developed grabens of two types. The first type (the Baikal type) is associated with the intensification of tectonic activity in the inland Baikal Rift Zone. The amplitude of vertical neotectonic movements, as well as the thickness of loose deposits reach their maximum here. Crustal movements in this area are still quite intense; they cause a high seismic activity with frequent and sometimes strong earthquakes. The second type (the Transbaikalian type) is represented by wide intermountain lowlands, which are very common in the Selenga river basin. They formed as a result of recent deep-seated tectonic dislocations superimposed on the rejuvenated Mesozoic depressions.

Intermountain basins are separated by mountain ranges varying in height and geological structure. They are noticeably dissected by exogenous processes of erosion.

In the Quaternary, the highest orographic units (the Baikalsky, Verkhneangarsky, Barguzinsky, Khamar-Daban, Khangai and other mountain ranges), especially their north-western and northern slopes, were exposed to glaciation, which is indicated by the presence of the alpine landforms (cirques, avalanche chutes, through valleys, moraines, etc.)

Both positive and negative landforms within the Selenga river catchment area basin and up to the Uda river mouth are generally directed northeastward with a dominant altitude lowering northward. The mountains surrounding of three Baikal intermountain basins (Barguzin, Verkhneangarsk and Khovsgol lowlands) are characterized by higher absolute altitudes and deeply cut river valleys. These factors predetermine a wide range of elements typical of mountain landform, or plain landform in the wide intermountain basins.

According to the geomorphological zoning [Highlands…, 1974; National Atlas of the Mongolian People’s Republic, 1990] the area of the Baikal basin is made up of the following features: Khangai and Khentei-Dauria highlands, Khovsgol mountains, Orkhon-Selenga middle mountains and its continuation in the north - Selenga (Selenginskaya Dauria) middle mountains, mountain systems of the Dzhidinsky mountainous region, mountain ranges of Khamar-Daban, Ulan-Burgasy, Ikatsky, Barguzinsky, Verkhneangarsky, Severomuisky, Baikalsky, and Primorsky, and the western side of the Vitim Plateau. Minimum absolute altitude is the Lake Baikal waterline; since it is regulated, it is subjected to slight fluctuations at around 460 m a.s.l. Maximum absolute altitude is 3,539 m a.s.l. (the Khangai Highland).

The highest mountain range in the area is the Khangai Highland located in the south-western part of the basin; it has generally subdued delineation and slight changes of relative altitudes. The mountains become more prominent towards the central part of the basin due to Alpine landforms. Tarbagatai and Telin-Tsagan are the largest northern spurs of Khangai Highlands with individual peaks reaching 2,500 m.

The maximum altitudes of the Khentei Highland mountains go up to 2,200-2,400 m a.s.l. Their wide and long spurs stretch westward and eastward, forming a large highland, gradually descending to low hills in the west and in the south, and joining the mountains of Transbaikalia in the north. Generally, this is a gently sloping landscape with wide-spread residual hills, rocks, and scattered stones. Traces of ancient glaciation are preserved to a limited extent.

The Orkhon-Selenga middle mountains are located in the central part of the watershed basin between the ranges of the Dzhida river basin in the north and the Khentei Highlands in the south. It features a flattened relief and its spatial configuration resembles a huge amphitheater descending towards the northeast.

The Selenga middle mountains consist of sublatitudinal medium-altitude mountain ranges with rounded summits (Tsagan-Daban, Borgoisky, Chikoysky, Tsagan-Khurteisky, Zagansky, and others) separated by wide intermountain valleys distinctly stretching along the main riverbeds. The valley bottoms are drained by the Selenga tributaries (Chikoy, Khilok, Uda, Dzhida) and composed of alluvial and proluvial deposits of different age arranged in terraces and wide piedmont plains. The Selenga river valley lies among low hills with granite residuals, rocks, and cliffs.

The Khovsgol area relief has a complex structure. Its west side features sharp-crested, steep-sided, and hard to access ridges of Bayan-Ula and Khoridol-Saryag. The outlines of the mountains to the east of Lake Khovsgol resemble those of the northern Khentei with altitudes over 2,000 m. Extensive Late Cenosoic lava plateaus are specific features of these mountains.

The Dzhida and Khamar-Damban Mountain Ranges have a lot in common. They stretch from the south-west to the north-east. In the west, they are relatively flattened and marked by bald peaks, gradually turning into the alpinotype middle mountains of the Big Khamar-Daban Mountain Range, which drops steeply to the shores of Lake Baikal. In the east, the mountains have a lower altitude. The Selenga river cuts through their spurs.

The northern part of Lake Baikal and the Verkhneangarskaya basin are surrounded by Alpine landforms with harsh outlines of the axial and piedmont parts of the Baikalsky, Verkhneangarsky, Severomuisky, and Barguzinsky mountain ranges. In spite of the relatively moderate elevations, there are many glacial traces here, and in some places there are small vanishing mountain glaciers (e.g. the Chersky Glacier – about 0.4 km2) The Vekhneangarsky basin relief shows little elevation changes at the bottom. It is formed by the alluvial deposits of the Verkhnyaya Angara (the Upper Angara) river, and by lacustrine alluvial deposits of paleobasins. Extensive proluvial and fluvioglacial piedmont plains are typical of the basin.

The structure of the Barguzinskya basin is typical of the Baikal-type depressions: large swampy plain areas at the basin bottom, and relatively uplifted ancient alluvial lacustrine terraces made of sandstone deposits. The presence of large areas of sandstone deposits predetermines high eolian activity.

In the south, the Barguzinskaya depression is framed by massive, but relatively flat landforms of the Ikatsky range. The highest summits of the Ikatsky range as well as those of the ranges lying further south (Ulan-Burgasy and Kurbinsky ranges) are treeless and flat with mountain terraces.

References

Logachev, N.A., Antoshchenko-Olenev, I.V., Bazarov, D.B. et al. (1974). Highlands of Cisbaikalia and Transbaikalia. Moscow: Nauka, 360 p.

Ecosystems of the Selenga basin (Biological Resources and Natural Conditions of Mongolia: Proceedings of the Joint Russian-Mongolian Complex Biological Expedition; vol. 44), (2005). Executive Editors: E.A. Vostokova and P.D. Gunin. Moscow: Nauka, 359 p.

Document Actions

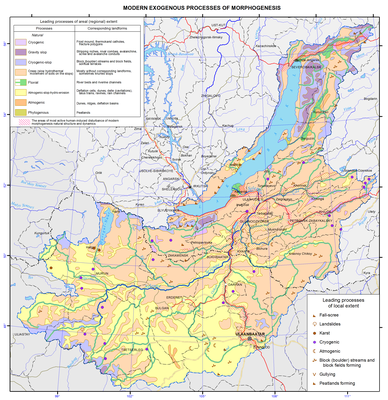

012. Modern exogenous processes of morphogenesis map

Contemporary exogenous processes of morphogenesis

For purposes of mapping, the leading processes were identified on the basis of a classification of the exogenous processes of morphogenesis of land, suggested by V. B. Vyrkin [1986], from taxonomic geomorphological units in accordance with the scale. At a small scale, the objects of geomorphological mapping are the types, subtypes and complexes of topography which are basic to identifying classes and groups of leading processes. The legend is based on identifying one leading process (the one exception to this rule is represented by the display of areas on the map where the contemporary morphogenesis is due to a combination of two leading classes of processes). Identification of the leading processes of the territory took into account their three main parameters: the coverage area, the duration of a continuous occurrence, and the intensity of development.

The process is identified through a process interpretation of the relief, deposits, landscapes, vegetation and other natural formations. The procedure brings to the fore the interpretation of the relief, its morphology, genesis and age, and the identification of the genetic types of deposits. Only an integral investigation into the landforms and correlative deposits, complemented with station-based observations of the intensity of processes, does make it possible to identify in the mapping procedure the leading processes, and of paramount importance is a knowledge of the geomorphological structure of the region being mapped. Vital to the generation of small- and medium-scale maps of the processes, especially for poorly explored spaces of Siberia and Mongolia, are space images. In Siberia’s remote regions difficult of access, space images provide the main information base for map compilation.

Thus the methodological framework for mapping the contemporary exogenous processes of morphogenesis involves determining and depicting the leading processes. Maps as produced by such a method offer a means of investigating the structure and functioning of the processes of contemporary exogenous morphogenesis. They can be used in developing and generating regionalization schemes for contemporary exogenous processes of morphogenesis.

The map as created on the basis of the aforementioned principles constitutes a wealth of information which can be employed in dealing with issues relating to rational management of natural resources, assessments of the relief and contemporary morphogenetic processes, and to implementation of measures for the protection of land surface against hazardous and adverse geomorphological processes.